The Language of Balance and The Language of Absolutes

by Rob Westerlund & Ruslana Westerlund

When it comes to politics and the mass media, it’s the rabid dog that barks the loudest.  News agencies make their profits by having a large audience watch their newscast and commercials. Every journalist worth their salt knows that to get a large audience, you have to provide entertaining and titillating news. Therefore, news stories and speakers are selected according to how loud, extreme, and polarizing they are. Some news networks’ bread and butter is presenting a polarized political point of view. However, to have a well-balanced understanding of politics and culture, it is more helpful to have speakers who are balanced and moderated in their approach to understanding and relating these important issues.

News agencies make their profits by having a large audience watch their newscast and commercials. Every journalist worth their salt knows that to get a large audience, you have to provide entertaining and titillating news. Therefore, news stories and speakers are selected according to how loud, extreme, and polarizing they are. Some news networks’ bread and butter is presenting a polarized political point of view. However, to have a well-balanced understanding of politics and culture, it is more helpful to have speakers who are balanced and moderated in their approach to understanding and relating these important issues.

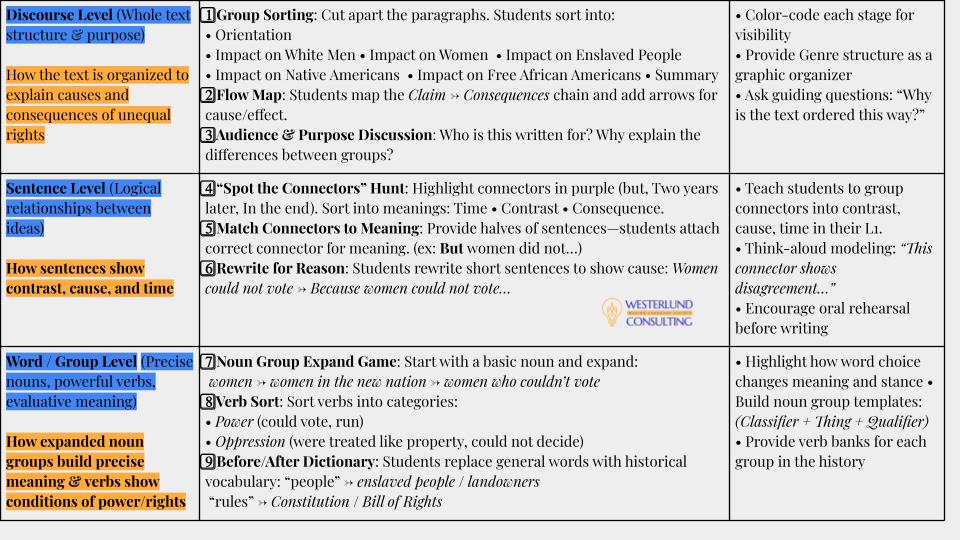

An understanding of Systemic Functional Linguistics can assist the listener in interpreting the message of an absolutist and possibly polarizing speaker versus a more moderate and balanced person. One of the benefits of being able to identify the difference between an absolutist and a moderated speaker is that a moderate speaker is less likely to use fallacious arguments, like appealing to emotion and fear, and more likely to present facts, precedent, and balanced personal views. But how do you identify the difference between an absolutist and a moderate by using a linguistic analysis of their discourse?

Systemic Functional Linguistics defines language as a meaning making resource. It views languages users as choice makers who use language to achieve their desired purposes. Let’s consider choices made by both absolutists and moderates in their discourse as presented in the table below.

Table 1. Examples of Language of Balance and Language of Absolutes

|

The Language of Balance “opening up spaces to other voices” |

The Language of Absolutes “closing spaces to other voices” |

| One would think | Everyone/nobody knows |

| It could be | It is |

| This might be true … | This is true! |

| On average, most people seem to… | Everybody does… |

| In most cases, generally | All the time |

| On more than one occasion | Always, never |

| It looks like, there will be a | It is undeniable |

| Some people find | Everyone thinks.. |

| Perhaps | Definitely |

| In an ideal world | This must happen |

| Although, | There is no excuse |

| I don’t know if I believe… | It’s definitely not |

| I feel as if | They must do this |

| More likely | You will |

| Be careful to | Always |

| According to experts | I know for a fact |

| I think … | The fact is |

| Probably | No doubt about it… |

The contrasting language used by moderate and absolutist speakers or writers illustrated in the table above, helps one to measure the approach an individual is using in relating political, cultural, and personal information. For example,

Moderate Speaker: I feel the absolutist may be more likely to harbor a strong, unconscious bias towards the subject matter they are presenting.

Absolutist Speaker: It’s obvious that the moderate speaker beats around the bush and must be blind to the truth everyone else sees.

What is demonstrated in the sentences above is the strategic care and precision of the moderate speaker in their language choices, in contrast with the curt and terse language choices made by the absolutist.

According to SFL, we represent ideas and cast interpersonal values every time we speak. Ideational and interpersonal are interwoven in every utterance. It is the degree or spectrum of “factuality” that differs between moderates and absolutists.

“Under systemic functional perspectives, … there is no utterance which is without interpersonal value. Nevertheless, the influence of the common-sense notion of the ‘fact’ is widespread and it may be tempting to see some utterances as more interpersonal than others. Under the heteroglossic orientation, however, we are reminded that even the most ‘factual’ utterances … are nevertheless interpersonally charged in that they enter into relationships of tension with a related set of alternative and contradictory utterances. The degree of that tension is socially determined.”

Using the Martin and White Appraisal framework, you can describe the balanced and absolutist language as “opening” or “closing” spaces. When a moderate uses language such as “it seems”, “apparently”, “I think”, or “probably”, it does not mean that they are evading the truth. It simply means that they are opening up spaces for interaction with other possibilities and other voices, using Bakhtin’s term, they are creating possibiilties for “heteroglossic dialog.” On the other hand, when speakers use language resources of high modality such as “have to”, “must” and over-generalizations like “never”, “always”, “everyone/no one”, they entertain an idea for a short time but quickly dismiss it, rejecting any possibility of a dialog.

Reflect on your language choices: do they open or close spaces for further dialog?

Rob Westerlund: Born in Pittsburgh and raised in Iowa, Robert Paul Westerlund is a writer, actor, preacher, college instructor, and public speaker. Rob is a college instructor who has taught many colleges courses, including Ethics, Critical Thinking, Logic, Humanities, and Film in Society. He has also worked as a minister of worship and pastor in Minnesota and Wisconsin, and a missionary in Japan, Ukraine, and Spain. His previous books include Hollywood Theological Seminary, City of Angels, and The Baka Geta Story. His most recent book is First Person Omniscient, a philosophical thriller, with a light touch of humor and a serious examination of the world we live in and the reality surrounding us we are all missing, all written in a rarely used perspective: First Person Omniscient.

Rob Westerlund: Born in Pittsburgh and raised in Iowa, Robert Paul Westerlund is a writer, actor, preacher, college instructor, and public speaker. Rob is a college instructor who has taught many colleges courses, including Ethics, Critical Thinking, Logic, Humanities, and Film in Society. He has also worked as a minister of worship and pastor in Minnesota and Wisconsin, and a missionary in Japan, Ukraine, and Spain. His previous books include Hollywood Theological Seminary, City of Angels, and The Baka Geta Story. His most recent book is First Person Omniscient, a philosophical thriller, with a light touch of humor and a serious examination of the world we live in and the reality surrounding us we are all missing, all written in a rarely used perspective: First Person Omniscient.

Ruslana Westerlund: Born in Buzhanka, Ukraine, Ruslana is a linguist, teacher, and thinker, and writer. She recently published From Borsch to Burgers: A Cross-cultural Memoir, available on Amazon. She is married to Rob Westerlund whose balanced language and perspective on very polarized issues has inspired her to describe his language in this blog.

Leave a comment