By Dr. Ruslana Westerlund

Over the years, as I have been training teachers on using SFL in their work as a toolkit for providing access to K-12 students to disciplinary meanings (it’s not the only concern of SFL to do that, but that’s what I’m asked to train on), I find that what I intend to convey, and what gets taken up are two different stories. That’s not a judgment of anyone, it is a description of learning. We hang new learning onto our existing schemas. If our existing schema says language learning is about learning parts of speech, and I say let’s identify expanded noun groups and how they add details in a story, then teachers hear “I must teach parts of speech like nouns”. New learning takes a great deal of courage and causes major discomfort, including disequilibrium, cognitive dissonance, and the like because new learning often has to undo the old learning. This is true to any new learning, from working out to pilates, or learning how to bake sourdough. When I was learning how to bake sourdough, I had to connect with the previous learning of baking bread and unlearn things like vigorous kneading, and speeding up the bulk fermentation with commercial yeast.

So, here I’ve decided to create a list of misconceptions about this powerful theory of language and I’ve synthesized them down to six.

Misconception 1: SFL is concerned only with academic language or the language of school.

Reality: SFL is centrally concerned with how language makes meaning and how it varies across contexts. In K–12 settings, this means talking with students that the ways we use language at home, in the community, with peers, and in school are all meaningful, but they serve different purposes. In K-12 schooling contexts, SFL cares about the expansion of students’ repertoires to develop “action literacies” – “a social process which enables students to engage with discourses, rather than passively consuming previously constructed knowledge. Genre pedagogies which illuminate the linguistic structure and features of disciplinary knowledge can foster action literacy” (Harman, 2018, p. xiii). SFL helps students see how to expand from everyday registers into the many registers of schooling—without losing the value of their existing repertoires. Translanguaging practices can play a key role here, allowing students to draw flexibly on their full linguistic resources to make meaning. For example, a child may first recount a personal story in their home language or through a spoken-like string of clauses, then shift into a more structured written recount for school. However, that shift must be explicitly scaffolded because language in the written mode is vastly different, and SFL provides a framework for seeing those differences and teaching students how to shift from spoken-like to written-like. (See here for more on that topic). In this video, you’ll see how to enact it in your classroom. In this video by Lexis Ed Lynette Lingard explains it with brilliant clarity.

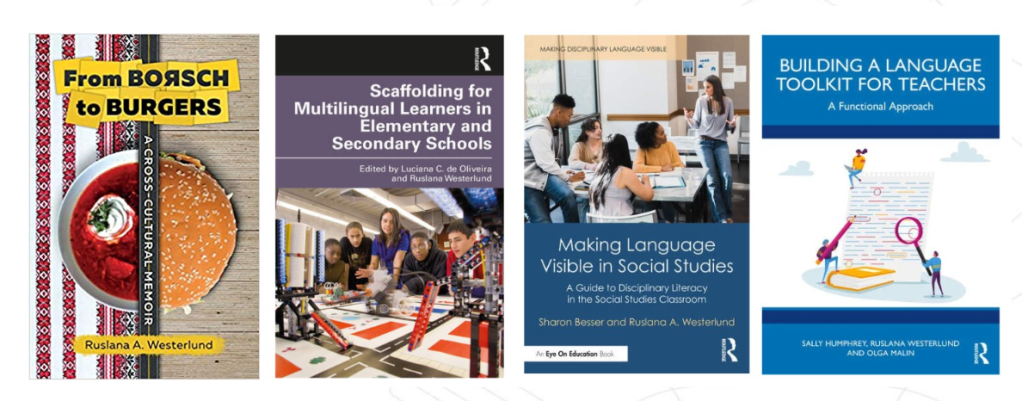

Misconception 2: SFL is only for multilingual learners.

Reality: While multilingual learners deserve an explicit language pedagogy that makes visible how meanings are realized through language, SFL is not only for them. All students—monolingual and multilingual alike—benefit from learning how language functions in context. In fact, it applies to you and me. Just notice how you make choices when you write an email to your boss next time. All those rewrites that you do is the choice making process. How should I start it? How should I greet them? Well, I don’t know this person, so I should briefly say something about myself, but how much is too much? What should I say as the first sentence? What should I put as a sentence opener: unfortunately, before I get to the point, with all due respect? Should I repeat this word for emphasis or should I replace it with a synonym?

SFL is a theory of language that systematically explains all those choices at three levels: the choices for getting the content of your ideas on paper (ideational), the choices for presenting yourself in a particular way (interpersonal), and the choices for threading the needle to connect your content and positionality choices into a coherent text (textual).

Success in school depends on mastering the language demands of different disciplines because the success of one’s graduation depends on it: the allegorical and metaphorical language of poetry, the dense noun groups of science, the buried causality of history, the logical and precise sequencing of math proofs, etc. SFL connects everyday and home repertoires with the register of schooling and reveals the “hidden curriculum of schooling” (that’s what France Christie said about language) that is often assumed but not taught (Maria Estela Brisk). (Putting comments on the margins “fix your flow and this is not clear” is not teaching. Giving students a CER graphic organizer in science and sending them off to fill it out is not teaching, it’s assigning). In a nutshell, SFL equips students to use language as a resource for building knowledge, enacting identities, persuading audiences, and participating fully in personal, academic, and civic life.

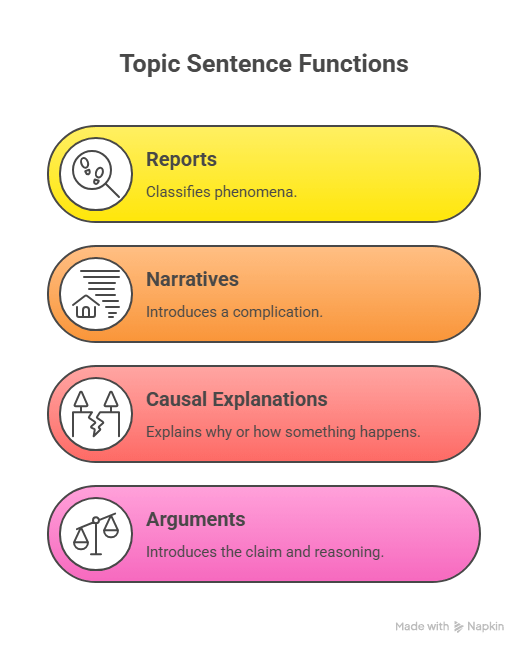

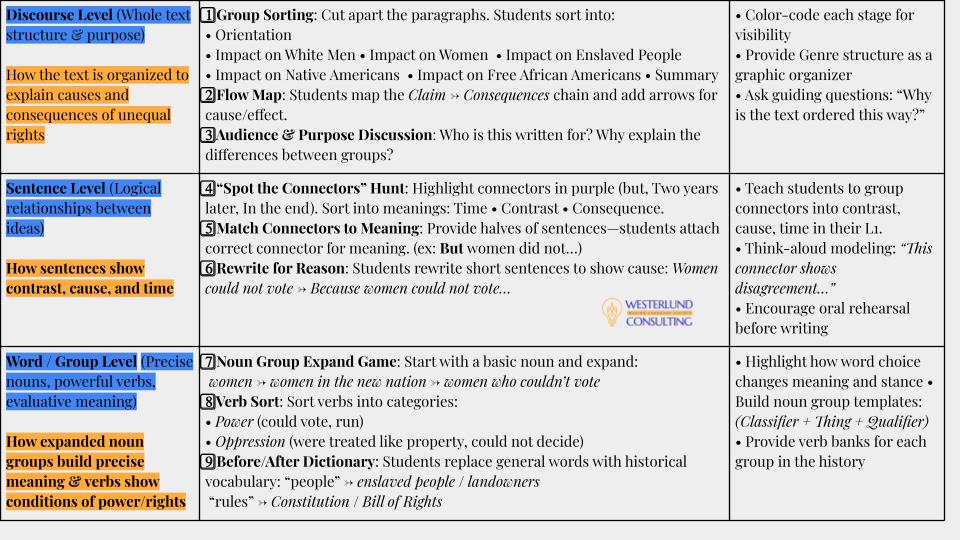

Misconception 3: SFL is just about finding nouns and verbs (or parts of speech with a functional tweak).

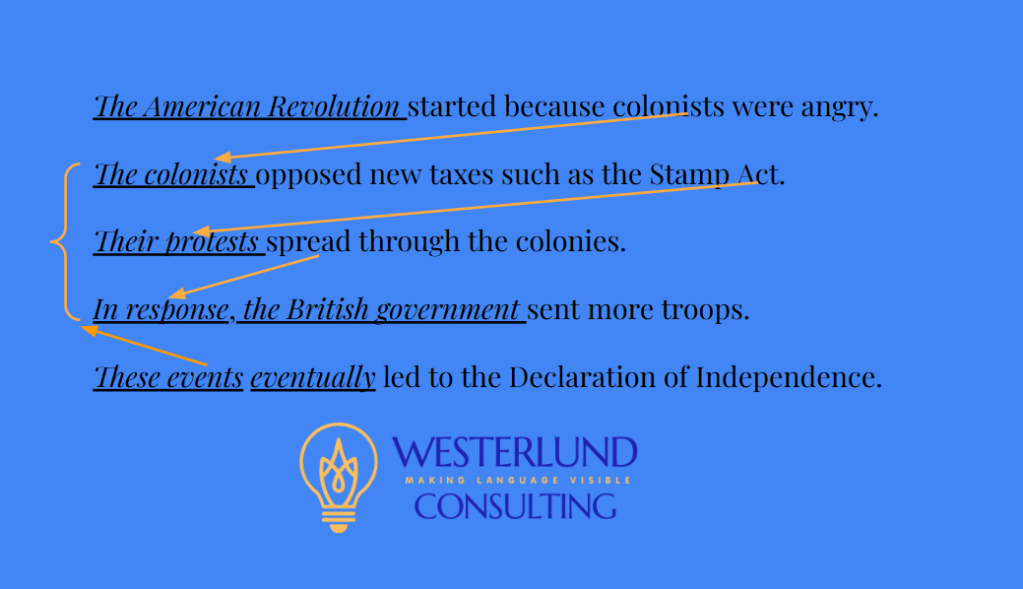

Response: SFL is not about labeling grammar but about analyzing how language works in contexts (what words do in texts)—how language functions to create meaning. For example, in traditional grammar students might identify “action words,” but in functional grammar we look at what meanings those verbs create. In stories, action verbs can build character feelings (she slammed the door → anger, he skipped home → joy). Adjectives, too, don’t just “describe”—they evaluate and judge (e.g., a brave soldier vs. a reckless soldier). Nouns in history don’t just “name”; they repackage actions into things, adding abstraction and sometimes hiding agency. For instance, “the destruction of the village” conceals who acted, unlike “soldiers destroyed the village.” This feature of historical discourse has been analyzed by de Oliveira (2011) and highlighted in the Reclaiming the Language blog as a way to teach students how history texts compress and obscure agency through nouns.

Misconception 4: SFL is only for linguists, not teachers.

Response: This misconception might stem from the belief that one needs to know all of SFL to do it right. But I what I have found in my work with teachers is you can do a lot with very little theory. I have been working noun groups with teachers across a variety of genres and content areas and we are able to do many things with one powerful language feature! (Blog with Lessons on noun groups.) Another stumbling block is the technical metalanguage. That technical metalanguage is used by linguists. When working with teachers and students, we can use what Sally Humphrey calls “bridging metalanguage” to create access points to the powerful ideas that the theory affords. However, we found in our work with students and teachers that students aren’t the ones who are afraid of metalanguage, it is actually the teachers because it differs from the “parts of speech” grammatical categories they are used. Meg wrote a paper “Miss, nominalization, is nominalization” where she describes how middle school students take up metalanguage easily.

Misconception 5: SFL treats language as the ultimate goal.

Response: SFL is not about teaching “correct” grammar or studying language for its own sake. Neither it promotes the “anything goes” approach. SFL promotes language as a powerful resource for our life, in the the service of something else. I can go back to my sourdough example. The reason I learn the language of sourdough is so that I can make sourdough and teach others including writing out a coherent recipe naming each stage correctly using the right language for the right job (e.g., bulk fermentation is different from cold fermentation). In school contexts, language is in the service of enacting roles and relationships between peers and adults, for knowledge building and communicating that knowledge, and for social action. Language is a tool to achieve other things, not the end goal.

At the same time, language learning is a goal because language enables students to act on the world. To do so effectively, they need to know which resources to deploy in particular contexts—whether to persuade an audience or enact a particular identity or to influence others. As Halliday and Hasan (1989) write, “Language is a political institution: those who are wise in its ways, capable of using it to shape and serve important personal and social goals, will be the ones who are ‘empowered’ … not merely to participate effectively in the world, but able also to act upon it, in the sense that they can strive for significant social change” (p. 44). SFL helps students develop this power by making visible how language works as a resource for knowledge-building, identity, and social action.

Misconception 6: SFL is only concerned with verbal language.

Response: SFL begins from the premise that “language is the essential condition of learning, the process by which experience becomes knowledge” (Halliday, 1993, p. 94). But it also recognizes, as Kress (2001) argues, that meaning is not made with language alone. SFL attends to how language works alongside other semiotic systems—symbols in math, graphs and charts in science, timelines in history, images in children’s books. Check out of my favorite videos on multimodality is by Gunther Kress in the References.

Out of those six myths I’ve identified which one is your favorite? Which one(s) should I add?

References

de Oliveira, L. C. (2011). Knowing and writing school history: The language of students’ expository writing and teachers’ expectations. Information Age Publishing.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. (2014). Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar (4th ed.). Routledge.

Harman, R. (Ed.) (2018). Bilingual learners and social equity. Springer.

Humphrey, S., & Feez, S. (2024). Grammar and meaning (3rd ed.). PETAA.

Kress, G. (2020, January 15). What is multimodality? [Video]. YouTube. “What is multimodality?”

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky: Vol. 1. Problems of general psychology (R. W. Rieber & A. S. Carton, Eds.; N. Minick, Trans.). Plenum Press.

Derewianka, B., & Jones, P. (2024). Teaching language in context (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Westerlund, R. (20). What does language do in history? https://reclaimingthelanguage.blog/2017/02/21/what-does-language-do-in-history/

Leave a comment