by Ruslana Westerlund

Children who speak different languages at home in the United States have been called many things. Some terms are more descriptive than others. Here is the list that I have heard in the 18 years of my educational career:

“Those kids”, “those Muslim kids”, “those Mexicans”, “those refugees”, “those immigrants”, “those kids whose parents don’t come to parent-teacher conferences”, “those kids who must be confused switching between two languages all the time and not speaking one well”, “those kids who don’t speak English”, “those poor kids whose parents need an interpreter, but we don’t have money to find one”, “children of those migrant workers who come and go”, “”those kids who always speak Hmong to each other”, and many other terms.

Those are terms that have been used by the general public and even worse, educators who subconsciously are engaged in “othering” or distancing themselves from “those kids”. Then there are terms that are used in language policy documents, in legal precedents, and in Federal and State laws. They are Limited English Proficient (I know so many Limited Ukrainian Proficient, don’t get me started), English Language Learners, English as a Second Language Students, English as an Additional Language Learners (EAL term is mainly used in international schools that use English as the medium of instruction), Culturally and Linguistically Diverse, and many others. One can trace a progression over the past several decades from seeing children as limited to viewing English as their second to describing English as an additional language which is the case for many families who have may have lived in colonized countries and grew up speaking different languages for different purposes in their lives.

You might say that we need terms and categories and labels to set aside funding, to create programming and to focus our energies on “meeting their needs”. However, I suggest that labels and terms are loaded with agendas that reflect societal values such as “We are in America. We speak English here”, carry an agenda that English is the only goal of these multilingual children and, as a result, leave an imprint on the children’s identity, i.e., how children begin to view themselves. The most recent term I heard was to describe semilinguals, children who have not mastered either language well. A term to describe those children was “Non-nons”. Here is an excerpt from the book Wright, W., (2010). Foundations of Teaching English Language Learners: Research, Theory, Policy, and Practice. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon Publishing.

“Non-nons is a term used in some schools to refer to Latino ELL students officially designated as non-English-speaking and non-Spanish-speaking. This designation results from language proficiency tests administered to students in both Spanish and English. Students who perform poorly on both tests are deemed as not having proficiency in either language. Teachers often buy into this construct, complaining about students who “don’t know English or Spanish. p. 128”

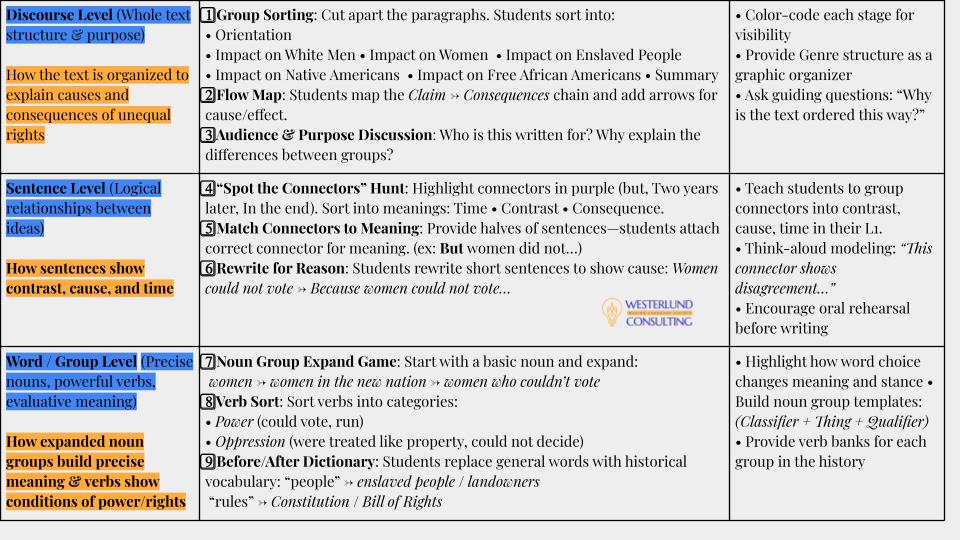

The photo I took from one of the many books I’m reading these days explains more. I will also write out the text below if the image is not easy to read. You may need to double click on the image to enlarge it.

“Linguistically, this is an absurd notion. All normal children (i.e., those without cognitive or speech-related disabilities) naturally acquire and master the language or languages of their speech community, typically by the age of five. p. 128”

“Jeff MacSwan, Kellie Rolstad, and Gene Glass (2002) investigated the non-non issue and determined that the problem is not children with no language but rather invalid language tests. They found that the tests gave heavy weight to literacy skills and standard Spanish. Students who spoke vernacular varieties of Spanish daily at home were deemed as non-Spanish-speaking simply because they never had the opportunity to learn standard Spanish or to read and write in Spanish. They concluded that language proficiency tests, and the resultant non-non labels, create a false and potentially harmful description of many ELL students” (p. 128).

Terms carry meaning and send harmful messages, they redefine how children view themselves. Language is one of our identity markers. It’s like clothes we put on with a purpose in the morning. We choose language purposefully too. We switch between different registers purposefully to identify with one group or another. I remember when I first moved to Madison from Minnesota, I learned that there is a special way to talk about Hwy 12. If you are a local, you call it The Beltline. At some point, I wanted to indicate that I was not “from here” and I used the term Hwy 12 to describe the route I take home from work. When I want to belong to the Madisonians, I switch and say The Beltline. It’s a simple example, but it should illustrate to you that we use language to say who we are even if the only language we are speaking is English.

I invite you to think about what is truly in a name when you talk about your students or hear other people talk about your students. Instead of looking at children as “walking deficits”, let’s change the way we view them. While acknowledging the need for English, the language required to access the power structure and contest the power dynamics in place in the United States, and the discipline-specific language to succeed in the schools in the US to be ready to enter college or make an informed choice about a career, we need to change the way we talk about kids navigating multiple linguistic repertoires. I think we should call them culturally and linguistically GIFTED. Garcia et al (2008) suggests we view them as emergent bilinguals.

References:

MacSwan, J., & Rolstad, K., & Glass, G. V. (2002). Do some school-age children have no language? Some problems of construct validity in the Pre-Las Español. Bilingual Research Journal, 26(2), 213-230.

Ruslana Westerlund, Ed.D. Ruslana has almost 20 years of ESL teaching experience at the K-12, undergraduate and graduate level. She is a proud immigrant from Ukraine who is fluent in 3 languages and has a rudimentary level of German. She is blogging to reconnect with teaching.

Leave a reply to Loving Language Cancel reply