by Ruslana Westerlund

The New York Times published an op-ed in 2015 analyzing the language used in the Texas History  textbooks published by McGraw-Hill Education. The “Grammatical choices as moral choices” phrase in my title came from that article. The NYT piece references this original post where Coby Burren, a 15 year old student, discovers that the authors in the Texas history textbook called “slaves” as “workers.” In addition, the whole conversation about “workers” is situated in the story on immigration portraying African slaves as immigrants who came from Africa as workers. This is an obvious case of erasure of African American version of history. His mom created a brief video and posted it on Facebook to show the audience the actual evidence of the textbook.

textbooks published by McGraw-Hill Education. The “Grammatical choices as moral choices” phrase in my title came from that article. The NYT piece references this original post where Coby Burren, a 15 year old student, discovers that the authors in the Texas history textbook called “slaves” as “workers.” In addition, the whole conversation about “workers” is situated in the story on immigration portraying African slaves as immigrants who came from Africa as workers. This is an obvious case of erasure of African American version of history. His mom created a brief video and posted it on Facebook to show the audience the actual evidence of the textbook.

One job authors of history books have is to produce a textbook. That entails a reconstruction of the past to tell their readers of “how things really were” and “to tell how it actually happened” (Coffin, 1998). However, during that reconstruction, “re-versioning” also happens, and new(ish) versions of history are created. The history is tinted through the lens of the author who makes grammatical choices that indeed reflect their moral choices. In other words, an author’s bias is written into the history. Also, when history textbook authors reconstruct their events, they also evaluate and re-evaluate them. What kind of language resources are available to them to reconstruct and re-evaluate the past in ways that suits their agenda? In her work on analyzing language of historic narratives, which I addressed in this blog, Coffin quotes Burke who said,

“More and more historians are coming to realize that their work does not reproduce ‘what actually happened’ so much as to represent it from a particular point of view. To communicate this awareness to readers of history, traditional forms of narrative are inadequate. Historical narrators need to find a way of making themselves visible in their narrative, not out of self indulgence but as a warning to their reader that they are not omniscient or impartial and that other interpretations besides theirs are possible. (Burke, 1991, 239)

Even though the C3 Framework for State’s Social Studies Standards encourages teachers to work with primary sources, the reality of most classrooms is that teachers still use textbooks.

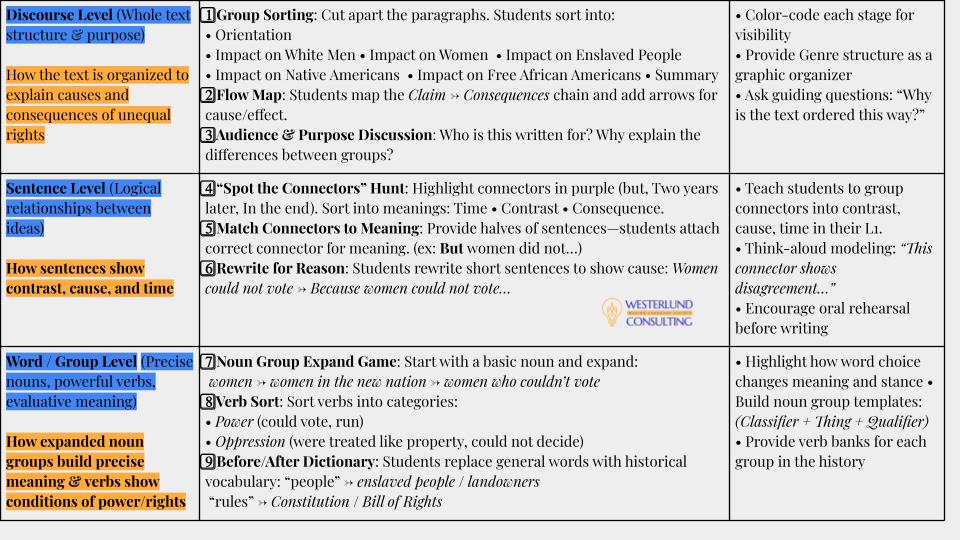

Despite the changing attitudes to the nature of historic knowledge such as that the US history, for example, is whitewashed, not much analysis of historic writing, however, has been carried out (Coffin, 1998). However, as teachers of history, whose job is to develop critical thinkers who can formulate balanced judgments about the value of differing interpretations of historic events in relation to their historical context and to “pose questions about a topic in United States history, gather and organize a variety of primary and secondary sources related to the questions, analyze sources for credibility and bias …” (Minnesota Social Studies Standards 7.4.1.2.1), the role that language plays in the construal of those interpretations and bias is not fully exploited by teachers.

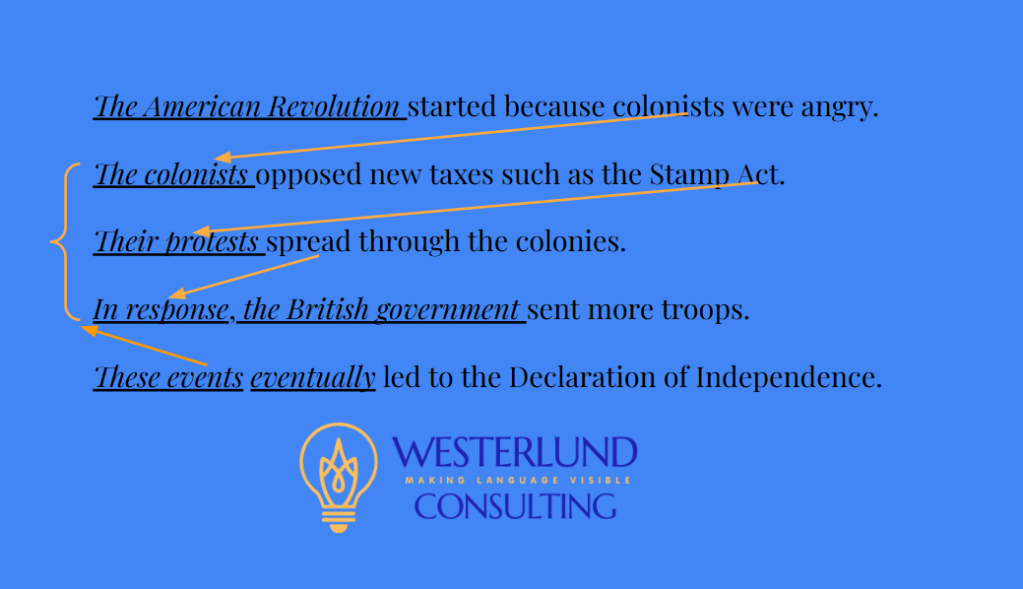

I had an opportunity to present to a class of 7th graders on how they can “see through language” and uncover author’s bias by using a very short text (Figure 1). They analyzed text without any problems and came to the conclusion that the reason authors write the way they do is because they do not like painting the history of their own country in a negative light. As a result, in this particular text they analyzed (Figure 1), slave owners get the credit for treating slaves with kindness such as providing shelter and clothing (part 1 of text below), but when it comes to negative actions such as whippings, torture, and branding – the agency is no longer made visible. We don’t want to name the bad guy. The exercise that I shared with students along with the “comprehension” questions are below.

Read the text and stop before the word “however”. Circle who is doing the action. Then tell your partner what kind of action is being done. Then read after “However”, who is doing the action? Why no people are mentioned here?

Figure 1. Text for Identifying Bias

Some slave owners reported that their masters treated them kindly. To protect their investment, some slaveholders provided adequate food and clothing for their slaves (STOP READING). However, sever treatment was very common. Whippings, brandings, and even worse torture were all part of American slavery.

Source: How Texas Teaches History, The New York Times, October 21, 2015

Students spend a great deal of time answering comprehension questions about historic events. ELLs often fill out worksheets to provide definitions of key vocabulary. Instead, we should teach them to understand perspectives and some facts are not as black and white and not that objective. Here’s a starting point for some of these questions (Figure 2): This set of questions deals with the topic of Westward Expansion, the topic my son will be studying soon in his class. I so wish his teacher engaged in these sorts of conversations with my son.

Figure 2. Suggested Language-Focused Questions for Critical Reading of Primary Sources

| Suggested Language-Focused Questions for Critical Reading of Primary Sources |

|

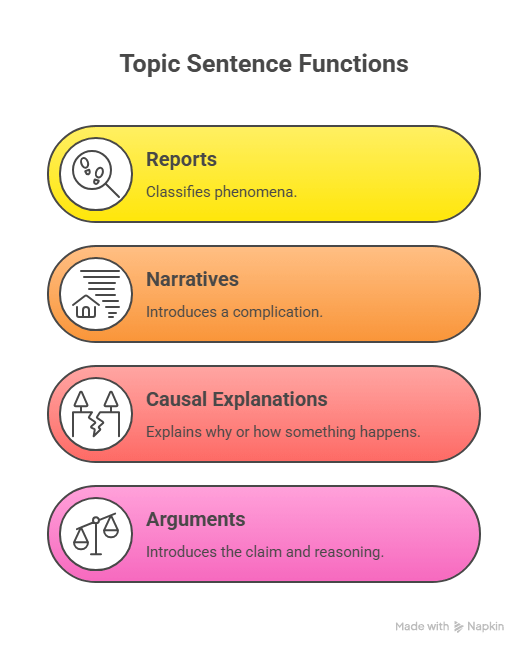

Teachers and students need to have a shared metalanguage to be able to understand and talk about the choices that authors make when they create their texts. Systemic Functional Linguistics provides a practical toolkit for teachers and students to analyze texts looking through the language lens. SFL asks students to always see language in context. SFL also asks students to think why out of all the choices that the author could have made, they made only those choices? de Oliveira (2010), in her work with teachers during the California History Project, produced an analysis of authors’ choices in discourse analysis of history texts from the SFL perspective by focusing on how authors used noun groups to package, condense, expand, and structure reasoning.

Before looking at individual words, it is important to talk about the context of what we are reading. The skills for contextualizing source are extremely important for all students as they develop skills to think like historians. After setting up the context, the next step is to look at sentences and then words WITHIN those sentences, not pulled out and worksheeted to death. For example, teach students to look at the whole sentence Families were often broken apart when a family member was sold to another owner. Then ask students “who did that?” question which will lead you to teach them the metalanguage for passive voice – a critical resource of many history and science textbooks. Students need to know the author made the choice to use passive voice were broken apart instead of active slave owners broke families apart to hide who committed such heinous act. In the clause “the removal of Indigenous children from their families” includes nominalization, a grammatical resource for turning an action to remove into a thing removal and discuss what function that achieved for the author. Why didn’t the author use the verb? What different meanings would have been achieved? Please don’t pull out your dusty grammar books and start creating worksheets on passive and active voice. TEACH LANGUAGE IN CONTEXT. There is no need to drill grammatical terms without any purpose. The only reason we need those terms is to have a shared metalanguage to use when looking at texts critically. After children understand what those terms are, they can create their own metalanguage as documented in several studies (Meg Gebhard, personal communication).

By taking time to look at texts critically in such a way that students will be able to “see through language” (Schleppegrell, 2017), we develop a generation of thinkers – a skill so important today in the time of “alternate facts”.

References and Resources for Further Reading:

C3 Framework for State’s Social Studies Standards https://www.socialstudies.org/sites/default/files/c3/C3-Framework-for-Social-Studies.pdf

Coffin, C. (2006). Historical Discourse. Continuum.

Coffin, C. (1998). Reconstruals of the Past: Settlement or Invasion? The Role of Judgement Analysis. Paper presented for the American Association for Applied Linguistics. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED421860.pdf

deOliveria, L. (2010). Nouns in history: Packaging Information, Expanding

Explanations, and Structuring Reasoning. The History Teacher (43)2 http://www.societyforhistoryeducation.org/pdfs/de_Oliveira.pdf

Schleppegrell, M. (2017) Linguistic tools for supporting emergent critical language awareness in the elementary school. In Harman, R. (2017) Bilingual students and social equity. Springer.

Leave a reply to Choosing a Language Focus (Example: Passive Voice) – Making Language Visible Cancel reply