Ever since I read Halliday, I realized how we not only misunderstood but entirely missed the role of language in education. We have reduced language to “language supports” or “language scaffolds”. We have reduced language as a meaning making resource to language as an inventory of structures leading to very unfortunate metaphors of “language acquisition” and created fields like “second language acquisition”, commodifying language and acquiring it like we acquire something outside of us. Halliday critiqued this metaphor years ago (see my blog from 2018). We have created language interventions needed “only for those kids, those who don’t speak English” as if English-proficient or “native English speakers” already came to school knowing various registers of math, science, art, or phyed. It seems like others have realized that and started putting slogans out there, Every Teacher Is A Language Teacher, but all we have is slogans, and language is still reduced to scaffolds and supports. In this blog, I’ll try to write why the problem persists.

One of the most influential ideas for this realization that language is more than scaffolds came from reading Halliday’s paper where he defines language as the “essential condition of knowing, the process by which experience becomes knowledge”. I couldn’t believe when my son (studying education now) texted me and said, Mom, you’re not gonna believe how this reading starts (Image below). (I’m so glad he is reading Halliday or at least about Halliday.) Back in 2016, I remember reading that quote twice, pausing, thinking and re-reading. In this paper, Halliday defined language in ways that were so new, so different from what I thought language was, that it led to unlearning and relearning. He defined it in terms of what it isn’t, and then what it its.

First, let’s unpack “Language is not a domain of human knowledge (except in the special context of linguistics, where it becomes an object of scientific study)”. What that means is that language is not an inventory of rules or structures that children must learn. Let’s learn auxiliary verbs on Tuesday. Let’s learn adjectives on Wednesday. When we look at the Common Core Standards for ELA, language is reduced to that inventory, no wonder we have a problem of language being an object of study versus language embedded into learning all things – ALL THINGS – from learning how to introduce yourself or how to be funny or how to sound like an expert when assessing art to learning how to navigate multimodal spaces when playing video games.

When you look at published instructional materials (often mistermed as “curriculum”), we find the same problem: Reading skills, Writing Skills, Language Skills. Everything is disjoined as if reading and writing are NOT realized through language. Again, it’s because language is misunderstood. It’s been reduced to an inventory of auxiliaries, adjectives, subject-verb agreement, etc. Most curriculum publishers reproduce the same misunderstood constructs of language that permeate everything else, perpetuating disintegration of language from learning.

When I talk to math or science teachers about language, they recount their traumatic experiences of diagramming sentences or learning rules as students. Because of that history, it becomes really hard to unlearn and re-learn what we mean by language in the service of math. The previous trauma becomes the filter through which all of things “language” goes through, and often gets rejected.

In higher ed, teachers learn how to be content experts, as if content is not construed through language. Of course it is, but if teachers were trained that language was an inventory of rules, then language has no relation to math or science or history or art. Then in those same higher ed spaces, in ESL programs, language is taught as scaffold or a support, even if there is a class called Lingustics for Teachers. My son says we learn Linguistics for Teachers and then we learn how to teach math but we never connect those two disciplines, as if math is a-lingual.

So, how do we build Language-Centered Education or Language-Centered Schools?

- First, we stop pretending that only multilingual learners need language.

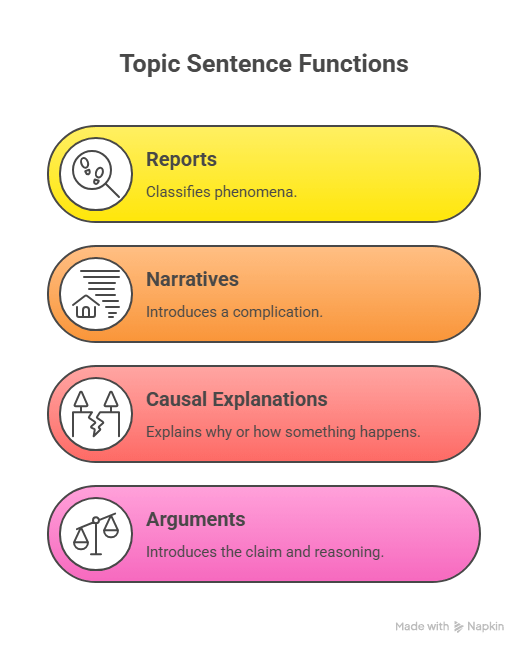

- Second, we recognize that language is the medium of all learning, not an add-on support—every subject teaches ways of meaning through language.

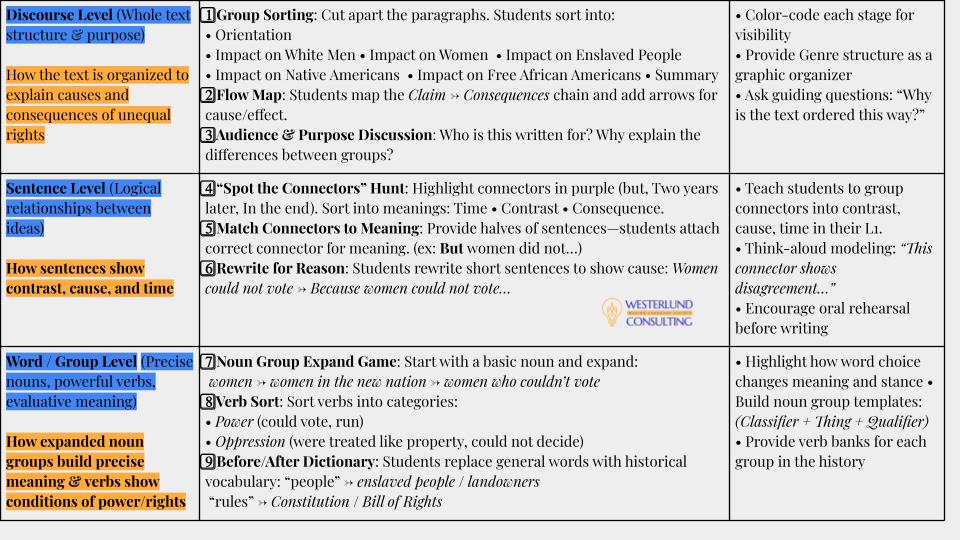

- Third, we make the language of disciplines visible: the genres, text structures, sentence patterns, cohesive devices that experts use to build knowledge.

- Fourth, we stop teaching language after the fact or before “content” but integrate it from the beginning through conversations about how language works across school day, not just in the literacy block but how language works in art classes, in technical education classes, or when we read, discuss, and write disciplinary texts.

- Fifth, we teach teachers—not just specialists—how to plan for content and language together, so every lesson includes both conceptual goals and language goals.

- Seventh, we position students as apprentices in disciplinary meaning-making, giving them repeated opportunities to practice the genres and language practices of scientists, historians, mathematicians, and literary scholars.

And no, we are not going to solve the problem of language education by reading Halliday outside of literacy coursework where we learn how children read, or math courseword where we learn how to teach math. Integration of language-based pedagogy must happen from the onset of program design where language takes center stage.

My book for Making Language Visible in Social Studies

Cheering you on,

Ruslana

Leave a comment